GeoSystems Global Corporation, an independent company born in the offices of Chicago-based problem solver R.R. Donnelly and Sons, eased  the headache of navigation on February 5th, 1996, when it launched MapQuest, the first website to relieve travelers of using unwieldy paper road maps. To plan a trip, an uncertain wayfarer could easily tap out the domain name on his computer keyboard rather than unfurling an atlas, then be guided to a site where a prompt requested his endpoint. Then, with a pluck of the “Get Directions” icon, a circular, lime-green “A” would appear, and here he would enter his point of origin. With a second click of the mouse on the “Get Directions” feature next, his travel menu would magically materialize, detailing the most convenient path through the country’s arteries, complete with highway signage and mileage tallies. At last, a trip planner could relax, fairly assured that he would arrive soundly, or at least without an unplanned stop at a local gas station to ask for directions.

the headache of navigation on February 5th, 1996, when it launched MapQuest, the first website to relieve travelers of using unwieldy paper road maps. To plan a trip, an uncertain wayfarer could easily tap out the domain name on his computer keyboard rather than unfurling an atlas, then be guided to a site where a prompt requested his endpoint. Then, with a pluck of the “Get Directions” icon, a circular, lime-green “A” would appear, and here he would enter his point of origin. With a second click of the mouse on the “Get Directions” feature next, his travel menu would magically materialize, detailing the most convenient path through the country’s arteries, complete with highway signage and mileage tallies. At last, a trip planner could relax, fairly assured that he would arrive soundly, or at least without an unplanned stop at a local gas station to ask for directions.

The fear of losing one’s way affects all varieties of travel. In foreign cities, a simple stroll to a local grocer can be handicapped by unrecognizable street names. Likewise, a bicycle ride through hilly, forested terrain can become oddly reminiscent of a Brothers Grimm fairy tale as roads begin to branch off, winding in different directions. Unfortunate, too, is that there exists no MapQuest for one’s lifestyle, either. Rather, each member of the human race is led along a wooded pathway of his own, where only his point of origin is known. Ever walking toward a nebulous endpoint, we can only look back reminiscently to account for each lively occurrence that goaded us forward, bringing us from there to here.

“I literally met my wife on the Champs-Elysees,” smiled Bistro Bordeaux owner Pascal Berthoumieux.” She was an American student who was studying French [abroad] for one semester only. After that first semester, though, she called her mom and asked if she could stay for another  semester. When her mother asked if there were a Frenchman in the picture, my wife [replied],’Maybe.’”

semester. When her mother asked if there were a Frenchman in the picture, my wife [replied],’Maybe.’”

Aware of the advantages of studying abroad, Pascal was equally savvy to the linguistic trades that occur when scholars re-locate to foreign shores. Upon graduating from a strict professional school in Bordeaux, Pascal stood witness as many fellow graduates left for England, where most would take advantage of the new setting to gain a fuller comprehension of English. However, like his future wife, he preferred French soil and remained, spending winters at Courcheval, a luxurious resort in the French Alps, and summers in Cannes, Nice, and St. Tropez. Eventually, he grew aware of a need to plant roots, though, and moved to Paris, where he began at The Barfly, a celebrity watering hole, before venturing into the truly fine dining room of La Maison Blanche. Located on the Rue Montaigne in Paris, it was right off of the Champs Elysees, where he met his wife.

“But the last place I worked in Paris was The Man Ray, which was opened by Sean Penn, Johnny Depp, the lead singer for Simply Red, and a few French investors,” he continued.” Two years later, I left everything and followed her here, [to] Champaign-Urbana, where we spent a few months before she graduated. It’s a small town with corn fields all around, so I was beginning to think,’’ he laughed,”‘ Oh, my God, what did I get myself into?’”

That summer, the pair traveled two-and-a-half hours north for a Chicago visit, an inspiring trek that foretold exactly what he had gotten himself into.

“I thought’,’ Wow, I could live here! Even though I didn’t speak English very well and had no idea where to apply for a job, when friends told me,’  Y’know what? Michigan Avenue! That is your Champs-Elysees!,’ I literally walked down Michigan Avenue, dropping my resume here and there.” The first inquiry Pascal received came from The Allerton, which eventually requested him to manage the food and beverage division of renowned French eatery, L’Escargot, housed inside.” But after being there a year, September 11th hit, and everybody lost his job. It was hard to find a job after that. But one day, Chris Ala, the executive chef at The Allerton, called and said,’ Pascal, I’d like you to come and open this restaurant with me,’ and that’s exactly what I did. I went with him to open his bistro and stayed for three years. We had a great time.”

Y’know what? Michigan Avenue! That is your Champs-Elysees!,’ I literally walked down Michigan Avenue, dropping my resume here and there.” The first inquiry Pascal received came from The Allerton, which eventually requested him to manage the food and beverage division of renowned French eatery, L’Escargot, housed inside.” But after being there a year, September 11th hit, and everybody lost his job. It was hard to find a job after that. But one day, Chris Ala, the executive chef at The Allerton, called and said,’ Pascal, I’d like you to come and open this restaurant with me,’ and that’s exactly what I did. I went with him to open his bistro and stayed for three years. We had a great time.”

To follow his term with Chef Ala, Pascal ventured to Chicago’s River North area, where he worked alongside Kiki’s Bistro owner, Georges Cuisance, “a Frenchman not unlike those who came to America in the ‘70’s around Maxim’s time.” Within three-and-a-half years, the pairs’ pursuits resulted in a peak in business and prospective plans to buy the twenty-three year old French favorite from its proprietor. But like the branching-off of roads as they twist through hilly, forested terrain, leaving one to wonder where he is standing, so an unexpected disappointment in the plan would result in finding a newer path.

Said Pascal: “Things didn’t turn out that way, in the end, and I decided to make it on my own. I never turned back.”

From there, the enterprising young Frenchman cast a decisive glance northward, eventually discovering a vacant storefront on Church Street in suburban Evanston. Its suitably boutique vibe jib ed with his sense of casual, urban class. Feeling a good fit, he began to quickly contact each party concerned with leasing security, city permits, and licensing, and opened Bistro Bordeaux’s doors forty-five days later. Here, he continues to lure the public away from its collegiate concerns, shopping lists, and family matters, all while providing for a family of his own. A true success story, Mr. Berthoumieux’s Bistro Bordeaux is a testimony to his stalwart refusal to turn back and assess the path that led him from Paris, France, to Evanston, Illinois, but instead to rely on the influences that carried him from there to here.

ed with his sense of casual, urban class. Feeling a good fit, he began to quickly contact each party concerned with leasing security, city permits, and licensing, and opened Bistro Bordeaux’s doors forty-five days later. Here, he continues to lure the public away from its collegiate concerns, shopping lists, and family matters, all while providing for a family of his own. A true success story, Mr. Berthoumieux’s Bistro Bordeaux is a testimony to his stalwart refusal to turn back and assess the path that led him from Paris, France, to Evanston, Illinois, but instead to rely on the influences that carried him from there to here.

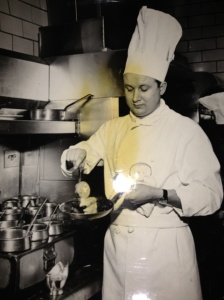

operation in 1979, its menu an appealing diorama of French cuisine. Diners chose a main dish from one of three categories, “Les Poissons”, “Les Viandes”, or “Les Grillades”, each with a vegetable garnish. As an accompaniment, they could opt for a few selections from a catalog of “Les Legumes” or “Les Pommes de Terre”, as well. And, finally, should they be inclined to indulge themselves, a septet of desserts awaited their choice at the end of the meal.

operation in 1979, its menu an appealing diorama of French cuisine. Diners chose a main dish from one of three categories, “Les Poissons”, “Les Viandes”, or “Les Grillades”, each with a vegetable garnish. As an accompaniment, they could opt for a few selections from a catalog of “Les Legumes” or “Les Pommes de Terre”, as well. And, finally, should they be inclined to indulge themselves, a septet of desserts awaited their choice at the end of the meal. opportunity ever presented. One of the first might have been Mrs. Kettering, resident-inventor Charles Kettering’s widow, quietly sitting across from Mrs. Beerman, a widow herself. Another may have been former WHIO news anchor Donna Jordan, doling out a dose of Champagne to mark her graduation from WDTN. In addition, were you to peer in the direction of Table Thirteen on that same night, you would not only have seen a gregarious regular named Ken, but heard his characteristically gruff voice, as well. Last, were you lucky enough to make it beyond the door on a handful of chilly November evenings in 1995, you would have borne witness to a cabinet of distrustful foreign dignitaries and their American counterparts, all endeavoring to help the embattled nations of Bosnia and Herzegovina reach peaceful terms.

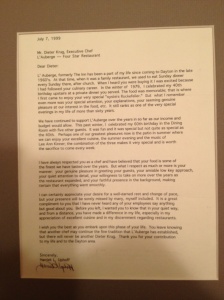

opportunity ever presented. One of the first might have been Mrs. Kettering, resident-inventor Charles Kettering’s widow, quietly sitting across from Mrs. Beerman, a widow herself. Another may have been former WHIO news anchor Donna Jordan, doling out a dose of Champagne to mark her graduation from WDTN. In addition, were you to peer in the direction of Table Thirteen on that same night, you would not only have seen a gregarious regular named Ken, but heard his characteristically gruff voice, as well. Last, were you lucky enough to make it beyond the door on a handful of chilly November evenings in 1995, you would have borne witness to a cabinet of distrustful foreign dignitaries and their American counterparts, all endeavoring to help the embattled nations of Bosnia and Herzegovina reach peaceful terms. birthday party upstairs at a private party you served…What I remember was your special attention, your explanations, your seeming genuine pleasure at our interest in the food, etc. It still ranks as one of the very special evenings in my life…

birthday party upstairs at a private party you served…What I remember was your special attention, your explanations, your seeming genuine pleasure at our interest in the food, etc. It still ranks as one of the very special evenings in my life… Thoughtfully considering the hours her father spent there and his contributions to family and community, Claudia related a sadness that was as familar to her as it is to the city her father served since 1979.

Thoughtfully considering the hours her father spent there and his contributions to family and community, Claudia related a sadness that was as familar to her as it is to the city her father served since 1979.